Behind The Scenes With The Biggest Soul Stars Of The 70s

7/22/2018 by Killian Fox (theguardian.com / The Observer – Photography)

Marvin Gaye, James Brown, Stevie Wonder – Bruce W Talamon photographed them all. His images, collected in a new book, capture an era before publicists controlled their stars.

Marvin Gaye, 1978: Marvin with his mother and brother Frankie. “She was slicing up a big turkey. She was just happy to see her boys and they were happy to be there. To think that that was the house where his father shot him six years later.” Photograph: Bruce Talamon

“Nobody will ever understand what fun we had,” says Bruce W Talamon about the decade he spent photographing the heyday of funk, R&B and soul music in America.

Between 1972 and 1982, this young and relatively inexperienced photographer from Los Angeles had almost unrestricted access to the biggest, brightest and weirdest stars in black music. He went on tour with Gil Scott-Heron, Labelle and Parliament-Funkadelic. He shot performances by James Brown and Diana Ross and captured intimate backstage moments with Al Green and the Jackson 5. For one assignment, he spent seven days with Marvin Gaye, hanging out at the beach, playing basketball and eating Thanksgiving leftovers at Gaye’s parents’ house. Today’s music photographers are lucky if they get 15 minutes.

His archive is a comprehensive and finely observed record of one of the most exciting eras in popular music. “I considered myself a chronicler of our history, of black folks’ music,” he recalls. But when Talamon moved away from music photography in the early 80s – first to do editorial work for magazines such as People and Time, and then to shoot promotional stills for the film industry – the archive went into storage and sat untouched for more than three decades.

George Clinton, 1977: ‘George came to our offices for this shoot. He was the one who stuck his tongue out, I didn’t ask him to. You had to be on the ball to capture those moments.’ Photograph: Bruce Talamon

In 2014, music writer Herb Powell, who was researching a biography of Maurice White from Earth, Wind & Fire, came to look at Talamon’s photographs of the band. “I started showing him the stuff,” says Talamon, “and eventually he says: ‘What else you got back there?’ ‘Ah well, I’ve got Marvin, the OJs, Chaka Khan and Rufus…’ And then you realise, oh shit, I’ve got something good here.”

Now, nearly 300 of these mostly unseen images – from magazine assignments and publicity shoots – are being published in a suitably weighty tome by Taschen. According to Talamon (and I couldn’t find evidence to the contrary), this is the first photo book that has ever been done on soul, R&B and funk.

Talamon hadn’t planned to become a photographer. “I had no formal training,” he tells me from his home in Los Angeles, during a phone conversation that spans two and a half hours. “I was a political science major, headed to law school. Then I bought a camera on an exchange programme in Berlin and got excited about the power of the image.” A year later, back in LA, he wangled a photo pass for the Wattstax music festival and shot Isaac Hayes wrapped in chains. More important, he met Howard L Bingham, a black photographer famous for documenting Muhammad Ali, who got Talamon in the door at the music magazine Soul.

Diana Ross, 1974: ‘This was at the Universal Amphitheatre in LA. Diana would do Reach Out and Touch while she was standing out in the crowd and the crowd would love it.’ Photograph: Bruce Talamon

“I fell down the rabbit hole,” is how Talamon describes his introduction to the febrile world of soul and R&B in the early 70s. “And it was a really special rabbit hole. First of all, these artists weren’t afraid to speak up. Think about some of the stuff they were writing, like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On: the music was being used to convey a message, it wasn’t all about shaking that ass.” Talamon feels that today’s equivalents suffer by comparison. “These were men who understood the power of protest,” he says of Scott-Heron and his contemporaries. “That is something that I haven’t seen enough of in this wonderful new generation of musicians.”

Then there was his access to these stars, which, he says, was incredible. “If you wanted to shoot Beyoncé or Justin Timberlake now, there’d be some publicist getting you to sign away all your rights. Also, if you’re shooting a live performance, you can only shoot the first three songs – get the fuck out! Half of the stuff I got that’s great happened during the last two songs of the set. And backstage, publicists didn’t snatch the Jack Daniel’s out of the artist’s hand or take the spliff out of Bob Marley’s mouth. I could shoot all night long and nobody ever said: ‘Put your camera down.'”

The Jacksons, 1978: ‘That was one of the first shoots after the Jacksons left Motown for Epic Records. We had music blasting… Look at the joy!’ Photograph: Bruce Talamon

Thanks to this access, Talamon was able to show far more than artists “screaming into the microphone,” as he puts it: he was also there for the quieter moments. His globetrotting section on Earth, Wind & Fire begins with the band’s exuberant, athletic performances – in one astounding stage shot it looks as if Verdine White has broken free of gravity – and ends with them winding down afterwards, playing air guitar or making late-night calls from a phone booth.

Then there’s the shot of a shattered Al Green collapsing against the door of his dressing room after a typically vigorous performance in 1977. “I only had an instant to get that shot,” says Talamon. “You have to be prepared.” There’s a wonderful quote from [jazz musician] Eric Dolphy: ‘When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone in the air; you can never recapture it again.’ Same thing with these photographs: if you see it happen, it’s too late.”

If vigilance was one of his watchwords, discretion was another. “The keys are: don’t fuck up the vibe and respect the artist,” he says. “That means: wait, wait, wait some more. If you’re in the room, you’re going to be all right. I didn’t bust in taking pictures.”

James Brown, 1973: ‘James gave you 150%, says Talamon. ‘When he was out there, he really worked it.’ Photograph: Bruce Talamon

Winning artists’ trust had benefits beyond the photographic. “Man, I got more private concerts than the law allowed,” Talamon laughs. “People like Marvin Gaye would say, ‘Listen to this’, and they’d play something hip. I’d be in the room when they were trying something out, working on some idea. Eventually I’d be like: ‘Aw fuck, OK, better take some pictures.'”

Being black was both a help and a hindrance. Talamon always felt he had to work harder than his white counterparts, and that making a mistake – failing to load the camera properly on a corporate job – would have far worse consequences for him. On the other hand, his racial background gave him something of a niche. “Sad truth of it was, the white photographers wouldn’t come out and shoot [lesser-known acts such as] the Dramatics or the Main Ingredient or War. Which meant we basically had the field to ourselves.”

Donna Summer, 1977: ‘I Feel Love was about to come out and Donna Summer was hot…’ Photograph: Bruce Talamon

The party came to an end for Talamon in the early 80s. “Things had started to change,” he says. “The record companies started asking for work-for-hire agreements, they wanted to own everything.” Friends in the business advised him to broaden his repertoire, so he went to work on film sets with the likes of John Singleton and Steven Spielberg, for whom Talamon shot action stills on the third and fourth Indiana Jones movies.

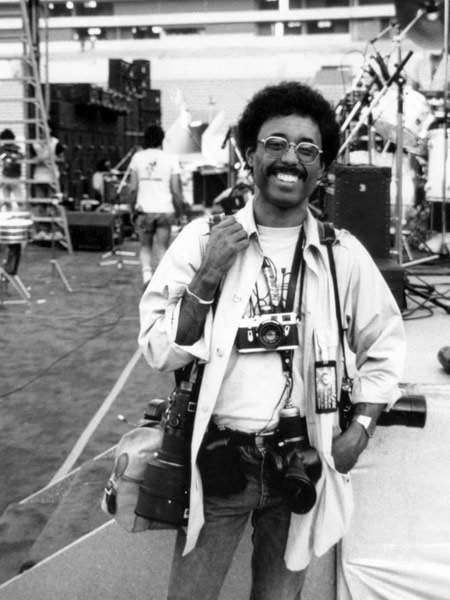

Bruce Talamon, Mexico City, 1979, during the Earth, Wind & Fire world tour. Photograph: Don Myrick

His music days continue to serve him well. “I make money licensing my work,” he explains. “I caught a lot of those artists at the height of their creativity and power.” Still, going back through his archive 40 years on was a bittersweet experience. “So many of these people are gone now,” he says, listing off Marvin Gaye, Maurice White, James Brown, Billy Paul, Natalie Cole and others.

In some ways, the book serves as a memorial for an age, and a way of doing things, that has been utterly lost. But Talamon is keen to point out that the music and the attitudes reverberate with no less energy today. “We’ve got a big show up at the Grammy museum [in Los Angeles],” he says, “and there’s a 12 by 20ft picture of Rick James on stage, cupping his ear to a crowd of 100,000 people. A little black boy walked up to this picture, he must have been six or seven, and I heard him saying, ‘Who’s THAT guy?'”

This is exactly the reaction Talamon is hoping for among viewers too young to have experienced that highly charged era. “I want people to see how badass Maurice or Marvin or Natalie was. I want them to think, wow, these guys were really having a great time.”