Bruce Talamon’s Photos Capture The Magic Of Soul, R&B, And Funk In The Seventies

9/20/2018 by Eric Ducker (Contributor – pitchfork.com)

Parliament-Funkadelic. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon.

When Bruce W. Talamon graduated from Whittier College in 1971, he told his family that he wouldn’t be going to law school like they expected. Instead he wanted to become a professional photographer, a decision sparked a year earlier while studying abroad in Europe, when he brought his new Pentax camera to a Miles Davis gig in Copenhagen. Talamon never took any photography classes, but his degree in political science meant he knew how to research. He stayed in Whittier, California, and got a job at Monte’s Camera, soaking up information from the other employees. In the summer of 1972, he finessed his way sidestage during Isaac Hayes’ headlining set at the legendary Wattstax concert.

It was at Wattstax that Talamon met Howard L. Bingham, who became his photography mentor and introduced him to Regina Jones, the publisher of Los Angeles’ SOUL Newspaper. Founded by Jones and her husband Ken, SOUL was a slim publication that featured the nation’s top African-American entertainers. Talamon became a contributor and eventually the photo editor, chronicling the music scene around his native L.A., which had been further invigorated by the relocations of Motown Records and “Soul Train.” He photographed such huge names as Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Parliament-Funkadelic, and James Brown, as well as many less-recognized acts of the time.

Talamon shot portraits, live shows, documentary images, and publicity snaps for SOUL, Ebony, Jet, and various record labels. The resulting images are, quite simply, astounding: vibrant, intimate, and somehow not part of the established music photography canon of the era. Looking at them now, you’ll wish you’d been staring at them for decades. The Grammy Museum featured an exhibition of Talamon’s work this past summer and on October 1st, the art-book publisher Taschen will release a 376-page collection of his photography, Bruce W. Talamon. Soul. R&B. Funk. Photographs 1972-1982.

By the early 1980s, Talamon had mostly stopped photographing musicians. Instead he developed a successful careful as an on-set photographer for films, chronicling the creation of movies that starred Eddie Murphy, Tom Hanks, and Denzel Washington. He also documented the presidential primaries for Time in ’84 and ’88. Though Talamon’s music work may be a revelation to discover, there is a hint of melancholy to it now, since so many of his subjects have passed away. That feeling was amplified on the day he spoke to Pitchfork, as that morning brought the news of Aretha Franklin’s death. What follows is a condensed conversation with Talamon as he looked through a completed copy of Soul. R&B. Funk. for the first time.

Pitchfork: When looking at these images, what do you remember more: the actual moments when you were taking the photos, or all the things that happened leading up to taking the photos?

Bruce W. Talamon: I remember most of what I was doing, most of what was going on. I’ve always told other photographers, especially young ones, “Pay attention. It’s all around you.” All the stuff you think might work,

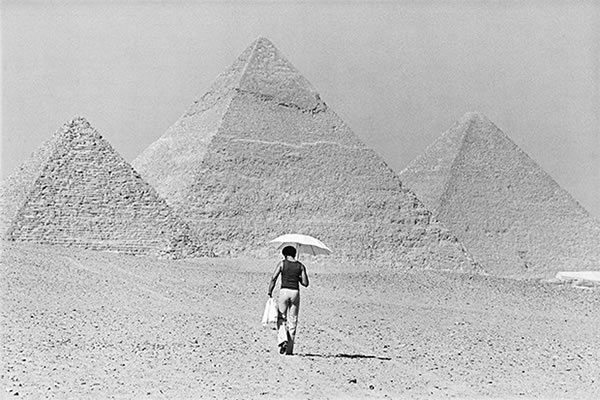

Maurice White of Earth, Wind & Fire. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon.

Like there’s Maurice White [of Earth, Wind & Fire]. Finally we finished the session at the pyramids [while touring with the band in Egypt] and he’s got my strobe umbrella and he’s walking back to the van and that’s when I saw it. I did something that you don’t do to Maurice White—I yelled at him, “Don’t say anything, walk towards the pyramid.” Then I just lined him up and shot off a roll of film. It became his favorite picture, and after he died it went all over the world.

What was it like photographing Aretha Franklin?

It was wonderful to watch her command a stage. She was really and truly the Queen of Soul; anyone else was just a pretender. And there were some bad women out there. You had Natalie [Cole], you had Diana [Ross], you had Chaka [Khan], you had Minnie [Riperton], you had all these heavyweights. But Aretha was the baddest of them all.

Aretha Franklin. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon.

This [portrait] was at her house here in Los Angeles. I vaguely remember she was cooking dinner, but it was really casual. She brought out some of her furs. She had a good time. We didn’t waste her time, either. Never tell them it’s going to take a half-hour, tell them it’s going to take five minutes, then they’ll give you the half-hour. The great photographer Bob Willoughby told me that, and when you look at his pictures of Elizabeth Taylor and Audrey Hepburn, you know it worked.

After we conned Regina [Jones] into buying the right lights, we could do the kind of photographs that we wanted. People looked at us differently. It wasn’t, “Oh, we’re going to take you outside and shoot you in the shade,” and then leave. They treated us like we were Rolling Stone or Vogue. Just that psychological effect [of having professional equipment].

Because of my own ignorance, I’d never heard of SOUL Newspaper until I learned about your book.

The black musicians loved SOUL and they loved Jet magazine. This was before Rolling Stone deigned to think about really covering black musicians. These black artists, they were speaking up. They understood the power of their position. I would like to hope that some of our younger musicians and celebrities might think about that and reassess. They weren’t afraid to ask for black photographers or black writers to interview them. As a matter of fact, they were instrumental in getting the black music departments in these record companies. All of sudden there were black executives up there. The O’Jays and Barry White and Donna Summer would say, “Where are the black people?” That was very critical.

Why am I saying all this? Because SOUL Newspaper put me in a position where these execs at these record companies would see me and they’d say, “Well, who’s that?” Then all of a sudden I get a call from their director of publicity who says, “We want you to do a shoot with Bill Withers.”

This book is not just black musicians sweating and screaming into a microphone. The [books that include black musicians] I’ve seen always have that. Now I’ve got that, I can do it well, but I wanted to show other stuff. One of the things I said to Benedickt [Taschen, founder and co-manager of Taschen] was, “There’s never been a photo book done on this. Ever.”

I imagine that over the years you’ve really seen L.A. change.

That’s true, so many historical spots [are gone]. Tower Records on Sunset, you could find Elton John in there, Stevie [Wonder], just going through the stacks, making their purchase like everybody else. That was something.

L.T.D. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon.

[Turning the pages, Talamon sees his image of 11-piece soul-funk band L.T.D. practicing at the house where they lived.] I love this, because it ain’t “American Idol.” The roof leaked, it was $200/month rent, it was up north by Pasadena, and they all lived there practicing their craft. This is the sweat. This is the stuff you don’t see. It isn’t every day Jimmy Iovine is in, giving you pointers. There was a sign [in the house] and it said, “Miss one day, you’ll know it. Miss two days, your friends will know it. Miss three days, everybody will know it.” That’s what these young people who say they want to be musicians better understand. That’s what the real deal is.

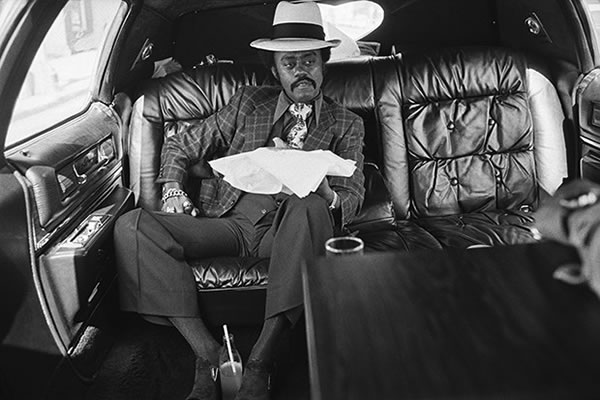

Johnnie Taylor. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon.

[Talamon continues to turn the pages.] This shot of Johnnie Taylor in the limousine in front of Pink’s Hot Dogs stand, that picture is important. In all of his finery, with his silk thick and thins, with his red soda, with his blue suede shoes. That’s a chili dog! That’s a Pink’s chili dog! We didn’t have but 14 pages in SOUL Newspaper and we did an opening spread of it. Regina was like, “Okay…” She was ready to kill us so many times. That’s the other thing, this book is also a love letter to Regina Jones. What I mean by that is she gave me opportunity. I went to Rolling Stone, I didn’t make it past the door.

Because of your race or because of the musicians you wanted to photograph?

I’ll just say that you see what I was doing. That’s the kind of stuff I showed them, but I never got any jobs. At SOUL Newspaper, I was home. [Regina Jones] basically just said, “Go out there and get something cool.” And oh boy, we did.

Look, man, I’m 69 years old. I’m sort of at the end of my career. I want to do books now and more projects. One day you figure out that you’ve got a good body of work that they can’t take away from you, and that’ll be there long after you’re gone. I tell photographers that if you can take care of your work, your work will take care of you.

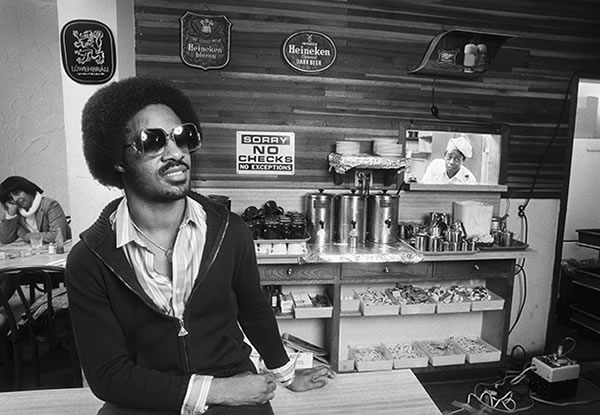

Stevie Wonder. Photo by Bruce W. Talamon.

It’s really incredible how many artists you photographed during this time.

That brings up another thing: How come I’m the only guy who’s got these pictures? All the music photographers knew who everybody was in town, but what I’m saying is, the white photographers would come out for the Jackson 5, they would come out for Diana [Ross] maybe, but they weren’t coming out for the Whispers and Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes. They weren’t down at the Crenshaw Palace for Billy Paul. Honestly, they weren’t coming out for Barry White until “Ally McBeal.” It was almost like someone was saying these musicians weren’t relevant. And they weren’t, to them and to their magazines. Okay, cool, but we were out there every night. That’s how I made my living for 10 years, and it was a very good living. Yeah, they came to see Stevie Wonder, but they didn’t get Stevie Wonder like I got Stevie Wonder.