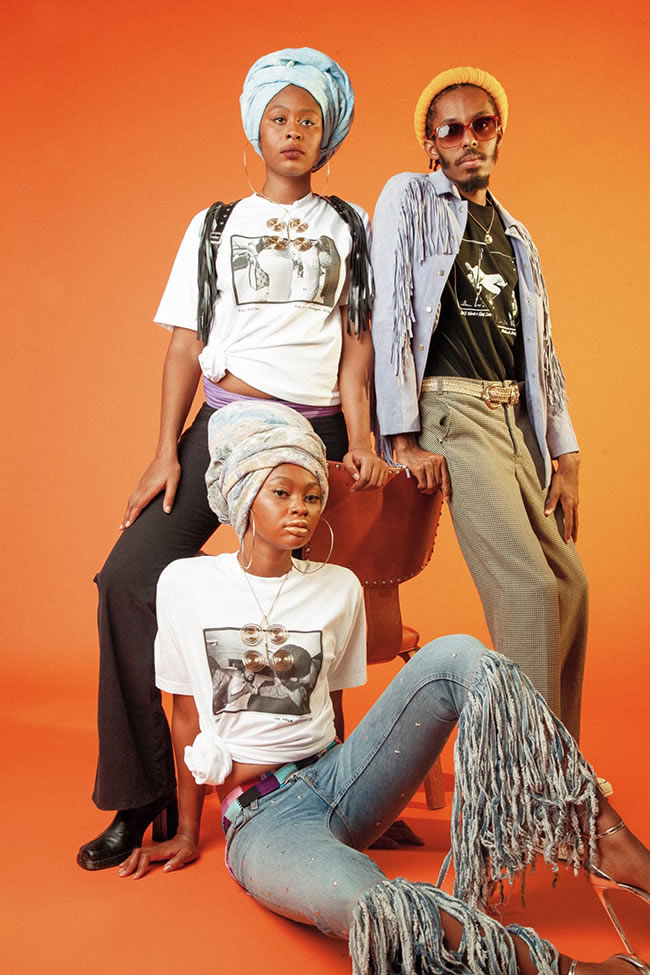

Amber Aisha / Courtesy of Union Los Angeles

STYLE: Bruce Talamon’s Photos Captured a Golden Era of Black Music. Now, They’re Coming for Your Closet

The photographer teams up with Union Los Angeles for a deeply cool collaboration.

By Chris Thomas – September 30, 2021

Over the years, Bruce Talamon captured images of Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross, Sly Stone, Marvin Gaye, and essentially every Black musician that defined the golden era of soul and funk music. For all Talamon’s influence, though, his name was new to Union LA proprietor Chris Gibbs when the photographer’s publicist reached out about a collaboration. Some digging led Gibbs to Bruce W. Talamon. Soul. R&B. Funk. Photographs 1972–1982, a book of his work published in fall 2018, and reconnecting him to an era he associated with his father’s dense record collection. But it also sparked an idea about a way to use Talamon’s images to tell a story that would bridge the gap between generations.

The result is a capsule collection of T-shirts emblazoned with Talamon’s photos of larger than life stars. Gibbs and his wife Beth “Bephie” Gibbs worked with the shutterbug to pick a series of images that would show Black culture in context, with a special focus on the incomparable cool that musicians of color have in their element. (The gear launches today at both Union and Bephie’s Beauty Supply.)

For Bruce, the use of his images represents a change – he hasn’t forgotten the grueling process of pitching a book idea that publishers deemed “risky.” Still, he explained in an interview alongside Gibbs, the whole thing feels good. “It’s a celebration,” he said. “There’s some pictures of people who aren’t here anymore. This is good. I’ve already heard from some people. Bootsy [Collins] is very excited that he’s going to be on a t-shirt.”

Amber Aisha / Courtesy of Union Los Angeles

GQ: Bruce, you’ve described yourself as “a chronicler of Black folks’ history.” Can you describe that role?

Bruce Talamon: Well, when you get to my age you finally, there comes that moment where you put your feet on the side of the bed, you sit there for a minute, and then maybe you realize that your work will stand. All right? I set out to make a visual document, and onet that not only would stand but it might educate. It might put faces to names. That was what I was looking to do. And that comes of course straight from the storytellers, straight from the griot, straight from … This isn’t anything new.

And for me, as I stated in the book, at one point, I was looking to go into law. But I liked the immediacy of the visual image and the record that is there. And I think later I heard this quote from Eric Dolphy, the jazz saxophone player, who said, “When you hear music, it’s in the air. It’s gone. You can never capture it again.” And I would like to think that maybe sometimes I’ve been able to capture moments – bright moments like Rahsaan Roland Kirk said.

With anything collaborative, you learn more about the person you’re working across from. What is something that you’ve taken from each other, respectively?

Chris Gibbs: I’ll start because I’m sure I’ve learned more from working with Bruce than he’s learned with me. But it’s been really incredible to work on this project. It’s something that we’ve taken a lot of time on—some of that is due to COVID, but I think most of it is because it’s something that is really important to share, and I wanted to make sure it was shared the right way. When going through the book, I really learned about story sharing. The book is huge: it’s thick and every page is a new story. Incredibly told, not only through Bruce’s pictures, but also through the kind of anecdotes that are offered. As you can already probably tell, Mr. Talamon is an incredible storyteller and he’s got a lot to share.

BT: Well you know, I’m thinking about how I discovered Union. I think I mentioned that my son was working across the street, and I’d sometimes drive by the store, and I’d always see these young folks lined up outside. I asked my son, who’s 29, “What’s going on over there, man?” And then he explained to me about the store and about what they were doing and it was something I’d never seen before, as far as how folks would line up to purchase this wonderful clothing, shoes, and stuff. I was fascinated by that, and then I did a little research. I will say that through this particular collaboration, which I’m extremely excited about, I was moved by Chris’ attention to detail. He just didn’t throw something out there. It was like, “Okay, what about this?” And it was indeed collaborative. Because I can be a pain in the ass.

CG: I wouldn’t say that, I’d just say you’ve got that attention to detail. Let me tell you the most nervous meeting I had, is when we had to present the T-shirts, the first proofs. I was just like, “Dang it, I really hope he likes these shirts, we put a lot into it.” And his first comments weren’t positive, they were like, “Hey, this is….” You know. And fortunately we had been looking at the t-shirts in the wrong light, so once we moved to the right light, [things looked good,] but your eye was incredible.

I think I’ve said this before, but at the risk of saying it again, the weight of your book and the weight of your work is not lost on me. And I’m humbled to be able to be a part of this through the T-shirts that we’re offering, and I wanted to make sure that they matched your work.

BT: Don’t be embarrassed. And I truly want to say this, there was a generosity there, all right. So, I felt very comfortable. This is the first legitimate use of my work on a T-shirt. Where someone has asked my opinion.

CG: I wanted to make sure to share him with everybody else now.

Bruce, you mentioned that your son introduced you to Union. And Chris’ kids are the coolest kids on the planet. How did having trusted younger perspectives around you inform the project?

CG: Well, there’s one photo that we chose that stuck out to me more than anything, which was Marvin Gaye in the back of a limo. I guess, because I have a 14 or a 16 year old that are listening to the worst crap ever… I’m really conflicted and I won’t digress too much, but I remember when I was growing up, whenever I put hip hop in, my dad was like, “What is this garbage?” So now fast forward 20 some years, and I feel like I’m just like my dad. But as [Gaye is] kind of laid out in the back of the limo and just the way he’s juxtaposed, I was like, “To me, that could have been a picture of Travis Scott today.” And so the reason why I really chose that photo is because I thought, although it’s Marvin Gaye some 30 years ago, it could be a contemporary artist today in the same limo. Maybe it’s a Maybach now, but … and just the way he was chilling back there, and my hope, and I’m pretty confident that that will be communicated and be appreciated to the younger community. Get that perspective by being around it. So yeah, I got a 14 year old and a 16 year old here at the house. The staff that works at the store are in their twenties, so we wanted to make sure that we were speaking to everyone.

Marvin Gaye in the limo.

Courtesy of Union Los Angeles

Earlier Bruce spoke about being a “chronicler of Black folks’ history.” Chris, given your role as as a Black man in fashion, do you consider yourself the same?

CG: Although my answer is no, you might be digging for this answer, which I’m pretty shy about admitting. For the sake of this conversation I’ll sheepishly say Union as a store, we’ve definitely represented a lot of Black and brown fashion designers. So, there’s definitely a place there where we’ve been maybe the sole representation or at least the kick off point for a lot of up and coming brands.

And because of my culture and because of the place I was in, that’s something I gravitated to organically. So, I’ll admit for better or for worse I wasn’t in there being like, “Yes, this store is going to represent Black people.” It was just organically representing Black people because, before I bought the store, I worked there and was the one in charge of buying, and that’s what I gravitated to. Those are the things that I was inspired by.

Why do you think Black art is considered a risky investment, when Black artists inform so much of culture at large?

CG: We’ve been so positive and so productive, but it’s kind of simple: racism and bigotry. It’s sad, but that’s what it is. It’s still something we’re struggling with on a daily basis. I don’t think many black people know the answer to that question, to be honest. I mean, I find myself asking why or how on a damn near daily basis. Like, “For what? Because my skin’s darker?” If you’re looking for the silver lining… It’s actually been detrimental to the people that are inflicting these decisions. It’s detrimental to growth. How America has treated Black people is detrimental to their growth in every single way, yet they continue to do it. I can’t remember who said it, but at some point I remember listening to someone who’s like, “Well, when I get called the N word, that’s not a…” I thought, “That’s not a me problem. That’s the person who’s saying it has a problem.”

And yes, that hurts us to hear it, and it hurts us when we’re kept out of certain spaces that we need to be in. The people that are believe these crazy thoughts, they’re the people that are losing out the most on what can be a really fulfilling and productive relationship.

BT: I would just say that there are certain facts that are staring you in the face, and are staring us in the face. I’ve been Black for 71 years, fellas. And I hope to be Black a few more after that, but you do see sometimes situations that you do scratch your head and wonder why. To what end? I think though—I know—that there is an abundance of caution, and business is business. But still, it is strange that people will put in money hand over fist for stuff that fails continually, and yet they won’t venture out to do something that might not be as risky as they think. I’ve often talked about an old guy who was a friend of my father’s. I was 14 or something. You know how you walk around the corner and your dad’s talking to somebody and that’s the grownups talking, but you end up kind of listening? The guy, he was a liquor salesman. But he could only sell to the mom and pop stores. He couldn’t sell to the big stores, big Pavilions or Safeway, stuff like that. He was doing the junior markets, the bodegas, the little spots. He said to my dad, “You know, Jimmy,” he says, “Just get me in the door, I’ll make the sale.” He also said later that, “If I do get in the door, I got to do the work.” And quite frankly, I think that sometimes we might forget some of that. We got to do the work once we get in the door. I’ve been fortunate to have been invited into many doors in my career… To be able to say that I have been a successful working photographer for over 40 years is pretty damn impressive, I’ll say.

But then I’ve also seen that other picture, too. To see people who I know who are wonderful shooters, and they never got the opportunity. There was a lot of frustration there. We’ve got to keep teaching and keep sharing and keep the new generation close. We need to pull them close and support them, and also tell them, “But you got to do the work. You got to be prepared. You can’t come in there screwing up, because you’re not going to get a second chance.” We don’t get the second chances. I lived in fear, brothers. I lived in fear.

Bruce, your art was created decades ago, then you brought it into this new era via your book. Now, with Chris’ help, your photos will live on as tangible pieces of clothing. I’m very interested in why you felt it was important to make Black art feel tangible and accessible today?

BT: There’s a couple of levels. From a historical standpoint, it’s important that we have a visual record. Interestingly, people talk about assets now. People talk about content. People talk about all this stuff that it took me a minute to catch up to, but now this stuff is worth something. Bob Dylan just sold his entire song archive for like $300 million plus. So all of this stuff does have a value.

It’s been nice to see that I have a body of work that’s worth something, and that we’re able to share it. That’s even better, that it’s been recognized now. The National Portrait Gallery just took one of my photographs, and it was last year, The Portrait of a Nation Prize, there were six given out. My photograph of Earth, Wind, and Fire was one of the portraits that was honored, and Earth, Wind, and Fire was honored. We were up there… I’m having dinner across from Jeff Bezos and Anna Wintour. It was wonderful… And Annie Leibovitz and folks like that, the great photographer, Mark Seliger. So I’ve been honored, and I’m just going to say to you, that’s my story and I’m sticking to it. So here we are. And that’s about all I got to say.

The title says it all: “Earth Wind and Fire Sideways…”

Courtesy of Union Los Angeles

We’re in this era of continuously sharing photos, and assets, and Instagram stories, and all these different places that things go, but there’s no attribution to the artist. Why was it so important not only to use Bruce’s work as source material, but to actually work with him and give him attribution, and to work on his collection?

CG: That’s a good question. To be honest, it never dawned on me not to. I’ve been in this business for 25 years, and I think one of the ways that I’ve been able to have the staying power is making sure everybody got their flowers. Much like we were saying a second ago about talking about racism, talking about, “How come it’s a risk for Black people?” And I was like, “Not only is it not a risk, you’d be way better if you really worked with them.”

Yeah, I could do a bootleg Bruce Talamon t-shirt, I suppose, and maybe I’ll get by, but it’s way more substantial, way more real, when it’s collaborative. I think we’re getting the full story here. It’s a holistic undertaking, and to me, that’s more special, and bigger, and it’ll stand the test of time, I hope and I believe.

BT: I wanted to follow up with one comment. I have a Facebook account. I have an Instagram account that somebody else handles. But one of the things about social media … that I have an issue with is the sharing, the taking, of photographs, and then putting them up all over the place. I understand fans, but also I’ve seen it used as promotion, I’ve seen it used to burnish a brand, and visual artists are hurting when people take that.

The power of social media is amazing, but who’s the guy who took the photograph? It might have been Jim Marshall, the great rock-and-roll photographer who shot Jimi [Hendrix] and Janis [Joplin] at Woodstock and Monterey Pop, or David Gahr, or Chuck Stewart, the great African-American jazz photographer. Oh, Lord, to look at Chuck Stewart’s work, brother, I want to throw my cameras in the water because Chuck Stewart … the stuff he did on Coltrane. And people don’t know about this brother.

CG: They know now.

BT: They know now, yeah.